By Douglas John Imbrogno | WestVirginiaVille.com | august2.2021

UPDATE: Since this article was published, “The Wake Up Call,” an award-winning documentary about Dave Evans’ remarkable life, received its world premiere in April 2022, at the Boston International Film Festival. The documentary will receive its West Virginia premiere Thursday, June 23, 2022, as an official event of the citywide FestivALL Charleston event in West Virginia’s capital city. (Purchase tickets here: bit.ly/thewakeupcall-tickets)

Dave Evans lay on the ground, looking up at the sky. He was 18. His life had just changed forever. Maybe he would be going back to Cabin Creek, West Virginia, where he was from. Perhaps the idea sounded good to him. Or maybe he wasn’t thinking about that at all.

There was tumult all around him. Gunfire. Bloody body parts. Marines dashing this way and that. Maybe he was going to die. He yelled encouraging words to his comrades. A radioman likely called in air support. A corpsman was needed. There were many fatalities. There was a Marine down who was still alive.

He wouldn’t be getting up again for a while.

The Bridge

Here is something Dave Evans once told a filmmaker. He says it on camera in the 2017 public TV documentary, “Vietnam: West Virginians Remember,” which included his experience as a Marine on the front lines in Vietnam.

“When you send an 18-year-old kid to war, and they cross that bridge from peacetime into wartime, there’s no way they ever come back. There’s no way. That bridge is burnt.

“You’ve changed forever.”

Ripples

Dave Evans died in Guatemala on July 3, 2020. He was 68. Word of his death rippled outward through social media. The ripples struck hard in Guatemala, in the American ex-pat community in Antigua, where Evans lived with his wife of two years, Kee Adams Evans. The ripples shot northward, through his home state of West Virginia. Many people there, myself included, still followed the remarkable odyssey of Dave’s life.

There was shock, grief. Expressions of deep loss. The word ‘hero’ — a word he always resisted and deflected — was invoked on many social media timelines. The ripples leapt across oceans, moved through continents. This is no hyperbole. If even a handful of the families and people touched by Dave’s work took notice of his passing — and you planted a red thumbtack where they lived on a world map — that would be one very red map.

In one of several interviews I did with Dave over the course of his career, of building and fitting prosthetic legs, hands and arms for thousands of people across the world, I asked him to list the countries where he had worked. He gazed upward, compiling the list in his mind’s eye.

“Nicaragua. El Salvador. Cambodia. Vietnam. Cuba. Sierra Leone. Ethiopia. Angola. And a little time in Tanzania,” he said. “Then in Iraq and Jordan, and a short time in Syria. The Republic of Georgia.”

He paused.

“There’s a lot of countries.”

As it was, he missed a few. In researching this remembrance, I reached out via email to his wife, Kee Adams Evans, in Antigua. I had met her when Dave returned to his home state for the premiere of that 2017 documentary, which aired on West Virginia Public Broadcasting. I sent Kee questions, mindful of her shock and grief. “I’m emotionally, mentally, and physically exhausted,” she wrote back. “We expected to have many more years together.”

Seeking a definitive list, I asked her where in the world Dave had worked, giving individuals back a version of their legs, arms, and hands made of steel and plastic, and the ability to walk out their front door again.

“We came up with a list a few months ago,” she said.

So, Dave forgot to list in our interview the following: India, Tajikistan, the West Bank, Peru, Russia, and his own homeland of the United States of America.

“He thought it was complete. But he said he could have forgotten some.”

No Harps For You

But first, this. If you’re a Short-Attention-Span reader, quailing at the length of this remembrance and about to bail, hang on for a few seconds. Listen to these few words from Mike Tallon, one of Dave’s good friends down Central America way. In the next few paragraphs, you’ll learn a lot about Dave in a few words and get a sense of the fierce devotion he engendered in friends around the planet.

For this is partly how Tallon said goodbye to his buddy on Facebook on the Fourth of July 2020, after he learned Dave had died at his home in Antigua, Guatemala, the day before, from what looked to be an accumulated avalanche of ailments:

“Dave shipped out for his next action last night. If I know him, he chose July 3 to prove his own independence from the nation that he both questioned and loved … My sense is that his afterlife is far more like being on ready-reserve, to go do battle with evil on some innocent’s behalf, than it is clouds and harps. He would fucking hate that shit. For Dave, this works better:

“Sleep Light and Haunt the Bastards.”

Scars

The front line Marine’s assignment was to attract enemy fire. A radio operator would then call in air support. It was an assignment not for the faint of heart. Only a thin slice of the large number of young Americans drafted into the Vietnam War faced this perilous duty.

“Only a fraction were out front under fire the majority of their tour,” Suzanne Higgins, who produced the 2017 documentary “Vietnam: West Virginians Remember,” told me when I profiled the program at the time. “Many were stationed back on base, had other supporting and very vital assignments, but weren’t out front with an assignment to draw enemy fire.”

For those on the front lines, it was not only a mortal danger, but a psychic one, said Higgins. “That kind of stress, tension, walking in jungles that are booby trapped, that are riddled with tunnels where the enemy just disappears — that plays havoc on your psyche. That leaves scars.”

According to the West Virginia Encyclopedia, 36,578 West Virginians served in the Vietnam War. Of that number, 1,182 died, a higher rate of death than any of the other 49 states in America.

Many more were injured, some grievously.

Ambushed

Dave was on the front lines in Vietnam in late 1970, from the start of August until Dec. 5. He was first trained as a mortarman with Company F, Second Battalion, Seventh Marines. According to the Bronze Star citation he would earn, his tour of duty was marked by “an exemplary and highly professional manner in several combat operations,” including Operations Pickens Forest and Imperial Lake. As a mortarman, he distinguished himself “by his courage and composure under fire.”

In early October of that year, he was reassigned to Company M, Third Battalion, First Marines. On Dec. 4, he led a squad of riflemen in the central highlands north of Danang, in a search-and-clear operation to rescue some downed American helicopter pilots.

“We were ambushed,” Dave said simply, in one interview I did with him years ago about that indelible day in his life.

He took a step alongside the dike of a rice paddy, triggering a land mine. An ambush followed. His world exploded, he later wrote. “War and injury came to me in a sudden moment of grenade blast and gunfire.”

He was blown into the air and onto the ground. With the exception of Dave and his radioman, all the members of the squad would die. “Particularly inspiring,” his Bronze Star citation, notes, is that “he verbally encouraged his companions to continue their mission while he awaited medical attention and evacuation.”

The dry language conceals a brutal scene. The mine blast scissored his right leg off below the knee. The ambush shattered his lower left leg. Too far gone, the leg was later amputated on the hospital ship USS Sanctuary. Only one thing was clear as Dave lay there. His former life as a greenhorn from the West Virginia outback had just ended, as he lay sprawled beside a rice paddy. He stared upward, in a moment he would describe decades later to someone he dearly loved.

Awaiting whatever was to come.

‘About 20,000’

Before I go further, I must admit something. Writing about Dave Evans’ life is intimidating, although I have done it a few times. But this story — which will, I suppose, be my last about him — will be a bit different, a sketch of the man from several angles, including his own words. And while he may have rejected the description, he was a hero to me. And I’m quite sure he was a hero to innumerable communities and people around the world.

What else could he be to the many children and adults who now have their freedom of movement back after it was ripped from them by land mines, gunfire, and the daily accidents of life? Dave once guesstimated for me how many people around the world he and his teams helped to walk once more. To lift and hold things again. To stroll down the street under their own steam.

Here’s that guestimate: 20,000.

A few years ago, right before he was headed to Tanzania, Tajikistan, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to teach, he told me he had probably trained more than 1,500 students as prosthetic technicians worldwide.

So, yeah. Hero.

Yet I don’t claim to be able to thoroughly plumb the depths of this complex, damaged, burnt-to-a-crisp, hard-drinking, hard-loving, globe-trotting Good Samaritan, and anti-war troublemaker. I was just a journalist friend he came to trust over the course of decades. I loved him, as so many who knew him did.

He was a touchstone for me. A smooth worry stone, actually, when I lost faith in the human race, freaked out by its abiding penchant for cruelty and chaos. If you could have your own two legs blown off below the knees, as a teenager in a war you didn’t understand, and then spend the rest of your life putting yourself at considerable risk in many a conflict zone, giving back to other people a simulation of their own legs, arms and hands, well …

Maybe there was hope for this species, after all.

At 17

Dave enlisted in the Marines in 1969. He was 17. He was not drafted, nor did he contemplate evading the draft, considered by innumerable young men at the time a swift ticket to an appointment with a flag-draped coffin. He was probably driven by his dad, or drove himself, the short distance from Cabin Creek in semi-rural Kanawha County to a recruiting office in West Virginia’s capital city of Charleston.

In one interview, Dave ticked off for me his reasons for enlisting as the Vietnam War raged. His reasons seemed unconnected, but he said they all added up. His dad had spent 17 years in the Navy, between stints as a coal miner. Dave had little interest in following his father’s footsteps down into the earth beneath the rolling hills where he had been born. Joining the Marines was a ticket out of town.

“It was a job. I was having trouble in high school. A friend of mine had been killed in Vietnam,” he said.

That is the exact sequence of his words. Trouble in high school. A friend killed in ‘Nam. Working class guys training as warriors with other working class guys. Those were the ones who heavily populated the front lines, fighting a war schemed up and executed by politicians and generals who were miles, countries, often continents removed.

Maybe he had some heroic urge to avenge his buddy’s death. Maybe he didn’t know exactly what he was getting into. But it sure would be different, whatever it was that lay on the other side of scribbling his name on a bunch of papers.

Back Home

It must have been a blur — an agonizing, confusing, painful blur — how he got back to West Virginia after his life blew up that December day. He was flown by helicopter from the front lines. Shipped by military transport across an ocean. Back, eventually, to Philadelphia Naval Hospital, for six months of physical therapy.

At some point he was discharged from the Marine Corps. He landed back amid the hills of home. Back in ‘The Mountain State,’ as West Virginia calls itself. It is an affectionate nickname that sidesteps the hillbilly tropes that dog its designated name. The phrase evokes the nestled safety and beloved reassurance of life amid its ocean waves of hills. But the former soldier back from war, learning to navigate a mostly rural state in a wheelchair, could not have felt much comfort.

What now?

He briefly got a job working in the office of Valley Camp Coal Company, in Shrewsbury, W.Va. Maybe his family connections to coal mining helped. At some point, he decided to pursue a nursing career.

FREE SUBSCRIBE to WestVirginiaVille’s e-mail newsletter:

WestVirginiaVille.substack.com

A view of life based in the hills of West Virginia, yet often ranging well beyond its borders in space and in time. | A multimedia web-magazine edited by DOUGLAS JOHN IMBROGNO with guest contributors.

First, he had to get steady on his feet again, to learn to walk with prosthetic legs. To adapt, in the meantime, to using a wheelchair, at a time when the needs and rights of people with disabilities were on few radar screens. He got advice from a friend, a lifelong wheelchair user from childhood polio.

“He owned a little bar up in Chesapeake, West Virginia — Corey’s Drive In,” Dave recalled in a 2017 interview. “He said, ‘Let me buy you a beer.’”

With a couple of cold brews sweating on the table between them, sipping and small-talking in their wheelchairs, his friend got around to some heart-to-heart advice.

“He tells me, ‘It’s going to be very difficult for you. You’ve got to be very careful not to let stuff get under your skin.’”

Dave took this advice to heart.

“That was a big help. That was the first counseling I ever got about being a person with a disability.”

Adjustments

One day in 1974, he came in to have his two new artificial legs adjusted at J.E. Hangar Prosthetics and Orthotics in downtown Charleston, W.Va. The owner must have been impressed by how this young man presented himself. He suggested Dave work there part-time. The young man agreed.

Now more confident on his prosthetic legs, Dave swept floors. Cleaned up. Did maintenance. He was good with his hands. In an email from Guatemala, Kee picks up the thread of how a door cracked open on a most unexpected globetrotting career for a coal miner’s kid from West Virginia.

“He had already worked in the coal mine and knew that wasn’t what he wanted to do. He fell in love with the engineering and the idea of prosthetics. He worked a two-year apprenticeship and was accepted to NYU Medical School.”

Dave studied in a post-doctoral prosthetics program at the New York school from 1979 to 1982. Much lay ahead for the student as he took what he learned out into the world.

Far out in the world.

The Haunted Generation

“We must never let another generation go through the pain and suffering we have! We are the working-class guys. We are the people whose children are going to die.” ~ Dave Evans, quoted in “LONG TIME PASSING: Vietnam & the Haunted Generation,” by Myra MacPherson (Doubleday and Co., 1984)

The Most Bitter

While recovering in Philadelphia Naval Hospital, he and other disabled vets had been contacted by Vietnam Veterans Against the War. “Because we were the most bitter and sensitive about what went on,” Dave explained in one interview.

Never shy to hold his tongue when there was something on his mind, Dave slipped easily into the role of anti-war activist. Of outspoken, speak-truth-to-power and screw-the-consequences spokesman. He became prominent in the growing anti-war movement in the early 1970s, teaming up with Bobby Muller and the Vietnam Veterans of America Foundation, along with Vietnam Veterans of America. He learned to say a lot in a few words.

“War,” he once stated in an interview, “is the obscene failure of people’s inability to communicate.”

He was invited to return to Vietnam and later to Central America as part of various delegations. He had found a niche. He had found his voice. Here is that voice, from a 2017 story in the Charleston Gazette-Mail, in which he advocated a full-bore draft for every young American.

Every single one.

“Everybody — 18 years old. Mandatory,” he said. “Two years of national service, regardless of sex, sexual preference, economic or social standing. Everybody goes.”

“War is the obscene failure of people’s inability to communicate.”

That would include, he made clear, the daughter of the congressman voting for weapons purchases for another country. And the offspring of the senator voting to dispatch American troops to a faraway land.

“His daughter, Suzy, is 18? She’s going into the Marine Corps. Sen. Williams’ son is 18? He’s going in to the Air Force. They all go serve. Now, when you’ve got kids, nieces and nephews, stomping around in a rice paddy somewhere, you might think twice about declaring war,” he said.

A rice paddy. Somewhere.

Been there. Done that.

How about your kids go this next time?

Making It

Dave first came across my radar in 1985. I was a young reporter for the Huntington Herald-Dispatch in West Virginia’s second largest city (which is to say, its second largest small city, since they’re all small). I covered the county government beat, but itched to write about something — and someone — with more gravitas than the County Commission’s controversial plan to de-fund the pumpkin festival. At the time, U.S. government backing for the ruling junta in El Salvador was a cause célèbre for progressive activists. Death squads and tit-for-tat atrocities by government forces and leftist rebels had caught my attention and concern.

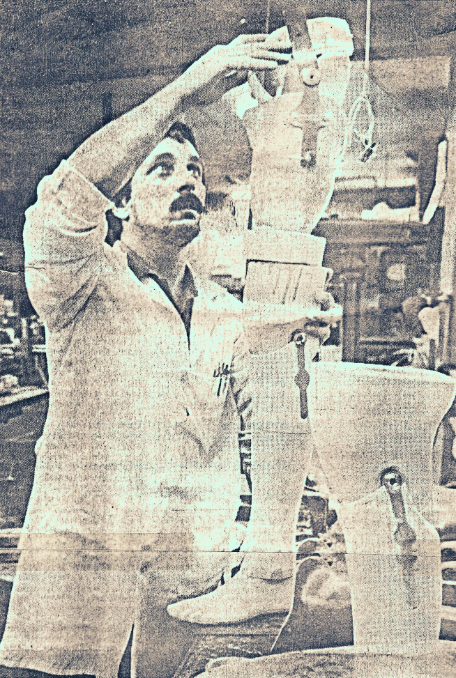

So it must have been through local activists protesting U.S. Central American policy that I first heard of this Vietnam vet one city over, conducting shuttle diplomacy of his own. A photographer in tow, I tracked Dave down one sunny November day, at Hanger Prosthetics in Charleston. He had just returned that September from El Salvador with the group ‘Americans for Peace in the Americas.’ What he was doing down there was about as ‘gravitas’ as any reporter could hope to find in the “itty-bitty” capital city of a backwoods state (as a musician pal once immortalized Charleston, W.Va., in song).

My first sight of Dave was of him tinkering with a prosthetic leg he had built. It was made to fit the stump of what remained of the left leg of an elderly man with an above-the-knee amputation. The man — who remarked to me on the fine Autumn weather in classic West Virginia-chatty banter — awaited its fitting out front.

Dave was not a big fellow — maybe 5-foot, 9-inches tall. He had short brown hair and a Tom Selleck mustache. He wore a white lab coat, jeans, and sneakers. My photographer captured a telling portrait of Dave. It filled a quarter of the page in the Sunday feature I later wrote. It depicts Dave in the back-room shop, surrounded by saws, hammers, screwdrivers, and work benches. It looks like he’s in a carpentry shop, an apt comparison since concocting prosthetic limbs is a muscular art and detailed craft.

Dave’s left hand props up the complex contraption he has fashioned for the man out front. His right hand fiddles with the brace at the top of the leg into which the man’s stump will go. Dave stares intently at the top fitting. When seated properly, the device would give the old man the ability to stow the crutches he had stamped into the shop with on that day, and to walk out under his own steam.

Dave has a laser-focus in his eyes. Studying my faded photocopy of that article from back in the day — published Nov. 3, 1985 and likely the only physical copy left in the world — it strikes me that I know that look. I have seen it from writing countless profiles of artists and craftspeople at their work when they are in the zone.

Their zone.

The potter at her wheel. The painter at his canvas. The chair-maker, smoothing with a lathe the cherry-wood leg of a chair-to-be.

The maker. Making something worth making.

Mistakes

Dave had finished work for the day. The old man’s leg needed more fine-tuning. The fellow had clomped out of the shop, hopeful soon to be done with the crutches after losing his leg from some long-suffered ailment.

“I love my country. But we make a hell of a lot of mistakes.”

These were among the first words out of Dave’s mouth as I began my interview with him in a bar next door. Dave, whose hitch in his walk would leap out at you only if you were looking for it, settled into a booth and ordered a draft beer. He massaged his legs near where they fit into the prosthetic legs below his knees. They were sore, he said.

He recounted for me the details I’ve reported above, about that day in Vietnam when he went down. The struggles that ensued. The bulk of our interview, though, was about the work he was doing for Salvadoran civilians, rebel fighters, and for government soldiers, too. For, besides the old man and his new leg, Dave’s corner of the Hanger shop included artificial limbs he was building to bring back to Central America.

“I love my country. But we make a hell of a lot of mistakes.”

His was an equal-opportunity mission of mercy.

He had hooked up with a fellow Vietnam vet, Charlie Clements, a former C-130 transport pilot, now a doctor and Quaker adherent of non-violence. In 1982, Clements slipped into rebel-held El Salvador for a year to treat villagers in the countryside. Upon his return, Clements formed Americans for Peace in the Americas, gathering a number of Vietnam vets under the group’s umbrella. In September 1985, they had toured Central America’s flashpoints with Dave as a part of the delegation.

They traveled to cities and towns in El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Honduras. Talked to government officials and soldiers. To U.S. military personnel and peasants. To fighters who had fled into the hills to take up the rebel cause.

Poor supplies and a jumble of weaponry marked the rebel effort, Dave said. Even so, the Salvadoran government appeared incapable of defeating the rebels, even with growing American military aid. The firepower included Huey combat helicopters, of the sort that likely ferried him into the sky in Vietnam after snatching up his bloodied body beside a rice paddy.

Dave, who appeared to possess the ability to speak with the poorest of the poor along with the highest-ranking power broker, said Salvadoran military leaders told him “they don’t see where a military victory is possible.” It all had echoes of the disastrous war America had launched in Southeast Asia, so memorably summed up in a word by one of its acclaimed chroniclers, David Halberstam: “A quagmire.”

That word-choice is mine, not Dave’s. But his palpable anger at the rising number of offensive weapons and military training the U.S. was pouring onto old fires in Central America vibrated from his side of the booth. The APA group visited disabled government soldiers, as recounted in a Sept. 17, 1985, Washington Post story. The rebel coalition, retaliating for what it said was government bombing and forced civilian evacuations, had strewn the countryside with land mines, the story said.

Dave heard of it firsthand. “‘We can’t fight them in the air, so we will fight them on the ground,’” one guerrilla fighter told him. For some Salvadoran soldiers, the mines meant the amputee ward. A surgeon told the Post that one government hospital was doing 15 to 20 amputations a month, mostly from land mines. The article described the excitement of soldiers in the amputee ward when Dave showed them his own artificial legs. He then ran a few steps.

“I talked to some of the kids who didn’t have legs,” Dave recalled. “What pissed me off is they don’t have prosthetic facilities to help them. That’s the kind of indirect military aid I would support.”

While on the ward, a Salvadoran colonel approached Dave and told him: “You lost your legs in Vietnam. The word is: ‘Death to all Communists!’”

Dave paused on his side of the booth in the bar. He fiddled with his beer, recalling the moment. He looked across at me. His blue eyes sparked with something between sorrow and determination.

“My response was, ‘No, Colonel, the word today is ‘Peace.’”

The colonel was quiet for a moment, Dave said. “Finally, he agreed. We shook hands and said ‘Peace.’ He learned a new word.”

Victims of conflict

If this were a movie (and award-winning documentarians Eric Neudel and Alison Gilkey will release a film in late 2021 on Dave’s life, “The Wake Up Call”) there would follow a sequence of images. Jungle towns. Battered historic cities. War zones. Territories whose precincts are in one warlords’ hands one week and in another’s the next.

In photographs, you can track the wide swath Dave and his teams cut as they bounded around the world. There is a photo of a white helicopter that fluttered him into one clinic in Sierra Leone. There he is, tenderly handling the stumps of childrens’ limbs in places as far-flung as Jordan, Ethiopia, and Nicaragua. There he is in Havana, the Congo, Russia, training a host of prosthetic technicians on how to do what he did. By leaving well-trained prosthetic technicians behind, the salvation of giving someone back their ability to walk and hold things wasn’t dependent on an American Samaritan, soon gone to another conflict zone.

Like many of his friends back in West Virginia, I would check in with him on social media: “You in the country, Dave?” Usually, he was not. He was in Iraq. He was in the Tajikistan. He had just spoken with Daniel Ortega, the triumphant revolutionary turned dictator-to-be in Managua, Nicaragua. Dave earned wide-ranging support for his work, from private foundations and U.S. State Department-aided organizations, such as the Polus Center for Social and Economic Development in Massachusetts. The group partnered with State’s Office of Weapons Removal and Abatement to address the toll of land mines and other explosives around the world.

It was a curious, almost poetic — if insufficient — recompense. The same government which had blown up so many lives in Vietnam, including putting one of its own in harm’s way, was helping that former soldier put people back on their feet again from war’s worldwide violence.

““The majority of my patients — 90 percent of them — are war-related.”

Yet he never glory-hogged his achievements. He pointed instead to groups like the Polus Center, Veterans for America, and fellow vet Bobby Muller. “I’m not the hero here,” he said in one interview. “I owe all this to the people who gave me a platform and an opportunity to do what I do.”

What he did in almost every quadrant of the world was to help soldiers of all sides, building and fitting them with new limbs. He worked with just as many civilians — newly limbless kids, teenagers and adults. I asked him once what the patients he worked with looked like. “The majority of my patients — 90 percent of them — are war-related. Landmine victims or gunshot victims.”

Yet in emergency clinics and rehab centers from the West Bank to Iraq, he and his technicians were not ones to turn anyone away. “You get a kid that comes in that blew his hand off with a firecracker or got run over by a car and is missing a limb …” he said. “You don’t turn them away. You’ve got all these trained technicians, and you’re going to tell the kid, ‘Sorry, you didn’t step on a land mine, we can’t help you.’ No, you bring them in and fit them and get them up and walking around again.”

Uncle Dave

At a clinic in Jordan, they called him “Uncle Dave,” an honor in the Arabic world. Uncle Dave was wrapping up another tour of duty — it seems appropriate to apply that military phrase to his post-military life — at a clinic in Amman in 2016.

“I had this one kid walk in — a bilateral, above-the-knee amputee,” he told me. “A kid with a lot of mental problems, a lot of trauma.”

Dave got him up and walking between parallel bars. He instructed assistants what to do next, since he was headed out of Jordan the next day and then back home to Guatemala. “I had two of my Syrian technicians there with me. I said, ‘OK, you need to do this, this, and that, because I’m out of here tomorrow. Get his legs up and keep him walking.’”

He needed to finish getting ready for his long journey home across oceans and hemispheres. At that moment, he noticed someone new had entered the room.

Someone small.

“I look to my left. And there’s a new kid standing there — with a leg off below the knee.”

Fuck.

“I broke down.”

He paused.

“You know, I don’t do that often,” he added. “This kid just put me over the edge …”

Uncle Dave caught his breath. Composed himself. Walked up to the boy. Knelt.

“When I get back, I’m going to make sure I work on you,” he told him. “I want to work on you when I come back.”

‘Una gran persona’

Below is a sampling of the huge outpouring of grief and homage on social media, once word got out about Dave’s death.

“Dave Evans was a supporter and frequent speaker at meetings of our Marshall University peace group, Marshall Action for Peaceful Solutions. At one of our meetings, Dave was speaking when he was suddenly interrupted by a couple conservative students, intent on disrupting the meeting. Dave listened to them for a while. Then, when he’d had enough. He said, “I may be a peacenik, but I’m not a pacifist,” as he walked toward them. They left shortly after. A dedicated anti-war activist and Marine until the day he died, Dave was always a warrior.” — Dave McGee

“This hurts a lot. He was a legend and real hero of mine.” — Mercedes Escobar

“Such heartbreaking news. I am so sorry. He was an admirable, indomitable man, in so many ways.” — Thea Hocker

“This is going to take a long time to absorb. I think I’ve been working with him through Polus for 22 years, all over the world. It is impossible to think of that work without thinking of the endless energy, enthusiasm, talent, knowledge, and commitment that Dave brought.” — Stephen Petergorsky

“Don David: Mil gracias for todos sus recuerdos quedaran grabados en nuestro corazon. Siempre fue una gran persona. (A thousand thanks for all the memories etched in our hearts. Always a great person.)” — Antonio Antonio

“Absolutely heartbreaking to hear this. What a man with enormous spirit, drive, and compassion for his fellow humans.” — Alison Heaps Gilkey

‘What’s this all about?’

Dave had three grown children from two prior marriages. I never came to know his now adult children, who live in West Virginia, or that part of his life story. Years would pass and then we would reconnect. I heard at some point he had moved to Guatemala. Once settled into Antigua, and into its ex-pat community of Americans, he met a woman named Kee Adams. Here is what happened next, as told from Kee’s perspective, in e-mail exchanges we’ve had since Dave died.

“Dave and I knew each other casually through Democrats Abroad Guatemala,” Kee recalled. “On the night of Dec. 21, 2016, we were both at a Winter Solstice Bonfire hosted by a mutual friend.”

She was headed out the door of the dining room. He was headed in. They began chatting. And chatting. “People had to navigate around us, just giving us a smile,” Kee said. “We moved into the dining room to get out of the way. And the next thing I knew he was holding my hand. I’m thinking, ‘What’s this all about?’”

They talked for an hour, him holding her hand all the while. As they finally parted, he asked her out. “He invited me to dinner the next night, to one of the nicest restaurants in La Antigua. We met each other there. He was so nervous! That was a surprise to me,” she said.

Just thirty minutes into dinner, he asked her to marry him. He asked two more times during the meal, said Kee. “I just laughed at him. I let him take me home. Being the gentleman he was, he gave me a sweet kiss on the cheek at the door and said it was ‘The best date ever.’”

She later accepted another of those offers of marriage. What attracted her to a guy whose life was spent hopscotching the planet, from one troubled hotspot to another?

“Probably those blue eyes. And his political passion,” she said.

“It was afterwards that I realized my fate meant nothing to those who sent me to Vietnam”

His main focus was, of course, his prosthetic work. As well as fittings he did with own hands, Dave was in demand worldwide to instruct in the art and craft of making prosthetics, often under the most dire circumstances. Yet he never abandoned his anti-war activism, Kee said. After all, it was war and human conflict that was the prime cause for all his hemisphere-hopping.

In interviews and newspaper columns, he often voiced his unvarnished view of war and the politicians who wage it. In one column, he wrote:

“It was afterwards that I realized my fate meant nothing to those who sent me to Vietnam. My experience is not unlike the experiences those young men and women disfigured and disabled in war will face — coming home to a country whose leaders forgot or ignored the lessons of Vietnam and dishonored us, who sacrificed life and limb in that war.”

He was, said Kee, “a ferocious progressive Democrat.”

In 2018, he began serving on the Executive Committee of Democrats Abroad Guatemala (DAGT), joining Kee on the committee on which she had served since 2015. Kee kicked him in the behind to join. One day, he was jawboning about the DAGT.

“I said, ‘If you don’t like the way we do things, run for Member-at-Large. Put your money were your mouth is, baby.’” she recalled.

“Of course, he won that election.”

Hero of the Open Heart

Mike Tallon moved to Antigua in 2004. He first met Dave at a joint there called Cafe No Se (“I Don’t Know Cafe”). It is a hangout Tallon describes as “a redoubt of romantics, artists, skells, vagabonds, heroes of the open heart, political activists, and social misfits.”

Dave was already a resident, said Tallon.

“I was tending bar and drinking there. Dave was a regular. But I actually got to know him around the poker table in the back room. Not just anyone could sit at that poker table. After a few months of getting to know the community, I was invited to the table, and once there I sort of came to know this oddball orphan’s family,” said Tallon in an e-mail exchange.

In 2005, the two did some political action work together, organized while at Cafe No Se. They helped instigate the first protest by American citizens in Antigua against U.S. involvement in the Iraq War, which was laying waste to that country at the time. Tallon recalled the protest outside the U.S. Embassy in Antigua.

“I remember Dave shouting over to the Marine guards that he was a Marine, too! And that he was called to duty in service of his conscience and the innocent people who would lose their lives for Bush’s incompetent, inhuman bullshit.”

Dave’s hang-time at the cafe lagged as he grew older, said Tallon. “After the first five or six years, Cafe No Se became less of a hub for him. I think, in part, it was health-related. We really did drink a lot back then. At some point, we either age out of that life, or we cash out.”

So, Dave pulled back, said Tallon, as he would, also, some years later. “After that, I didn’t see him much, but we remained close.”

His favorite story about his friend, though, dates from their primo drinking days. The year is 2006.

“As you know, Dave didn’t advertise widely that he wore prosthetics. So, a friend could go, literally, years without knowing the guy had no legs. Which is relevant to the tale,” said Tallon.

The two friends were at a bar in Antigua called El Muro.

“It’s me, Dave, our friend, Annie, and her brother, Mike, who is visiting from the States. Mike is a kid, maybe 19 years old. He’s sort of a giant puppy, at the time. Physically imposing and green as the grass by the piss tree.”

The subject of bar bets arises. The gringo teenager doesn’t know what they are, said Tallon. “So, I explain a bar bet is a seemingly outrageous wager that the mark is guaranteed to lose.”

The boy doesn’t get it.

“So, we run a few on him. Put a coin in a bottle. Three pints vs. three shots. The usual. Each time we run them, we make sure he’s the mark and it costs him a bit of money or drinks.”

Tallon has some heart-to-heart advice for young Mike.

“I tell him, very specifically, that if he’s going to lead a drinking life, then he’s got to understand that if a man bets you that ‘In five minutes a monkey will run up your arm and piss in your ear,’ then you believe him. Because, sure enough, in five minutes a monkey will run up your arm and piss in your ear. It’s the nature of things.”

Young Mike seems to get it.

“But an hour later,” Tallon continues, “Dave circles back around and tells Mike that he’s got one more bar bet for him.”

Dave points to the far wall of the bar, said Tallon. “And says that he bets he can touch that wall with his feet, while stretching out and touching the other wall of the bar — a good 30 feet away — with his finger.”

Young Mike hems and haws.

“He knows about the monkey. He’s already lost half a dozen of these things. We counsel him not to do it.”

But the boy is all in. He puts Q100 in Guatemalan dinero on the table as his wager — about $12.50, at the time. Says to Dave: “Well, do it.”

Tallon described what happened next.

“Dave calmly unhooks his legs and hands them to me. Then, he hops off his stool and waddles to one wall, while I walk the legs over to the other one.”

They touch opposite walls of the bar at the same time. The loser of this prosthetic-engineered bet was a good sport, said Tallon. “Mike laughs, Dave comes back over. We all have a round and a laugh on the kid.”

Tallon added this postscript.

“Afterwards, when the conversation moves on, I ask Dave if that’s a trick he’s played before? He said only once — in a West Virginia bar, a few months after his rehab for his injuries.”

Dave did not say it exactly, Tallon observed. “But he did infer that playing that trick all those years ago back home was an important inflection point in his trajectory.”

What trajectory?

“It’s sort of when the whole ethos of ‘it ain’t nothing but a thing’ sunk in with him. Or it seems that way to me.”

‘It ain’t nothing but a thing.’

Tallon explained further. Seven years ago, he almost died from a genetic disorder. “It put me into heart failure, pancreatic failure, and gave me Stage IV cirrhosis. And for sure, the drinking didn’t help.” He was not expected to live. “But I did. After a year of fighting for my life in New York — hospitals and family were required — I made it back down to Antigua.”

Time for a celebration.

“At my 50th birthday party, the whole town is there, including Dave. After a few hours, he buttonholes me and we sit down to talk. He tells me that now I understand what the guys in Vietnam always said: ‘It ain’t nothing but a thing.’”

After nearly buying the farm, Tallon thought he understood what his friend meant. Dave and other veterans learned this hard truth in the jungles of Vietnam, he said. “They learned that at some point, this world WILL kill you. You do not have any choice in that, AT ALL.”

This was an e-mail exchange, but if Tallon had been telling me this in person, I imagine he might pause. Eyeball his listener for the clincher.

“His meaning was this: At some point in life, all the bullshit gets stripped away. You learn what literature knows as ‘Snowden’s Secret’ from ‘Catch 22.’ That when the spirit is gone, man is matter. Drop him from a high place, he falls. Throw him into a pit, and he rots like the other garbage. Set him on fire, and he burns. Once you accept that — really fucking accept that — then everything that doesn’t kill you, well …

“That ain’t nothing but a thing.”

He added:

“You move on. You go to the bar. You don’t get too upset by the asshole on your right or your left. If you can, you use what you’ve got and you win the bar bet, so that you can have a laugh, make a new friend. And then do the important stuff. Like continuing to wage war on the sons-of-bitches who treat folks like us as if we don’t have souls.”

Somewhere in all that, he said, “there is the truth of the guy I knew.”

Dave Evans was a warrior, said his friend.

“He knew the the world was going to take his life at some point. But until then, he’d rage with an open heart and powerful sword.”

‘Please continue trying not to harm each other…’

Here are some final snippets in Dave’s direct voice, before this memoriam wraps up with a story from the day in Vietnam that set his life’s course and led to his global work as — a noteworthy phrase he once used — “a rehabilitation specialist.”

The first comes from a dispatch for La Cuadra, a magazine published out of Guatemala by Mike Tallon and another friend, John Rexer. Dave was writing from Basrah, Iraq, in Summer 2013. He signed the piece: “Dr. David Evans.” It is worth printing in its entirety. For all his seriousness, it conveys Dave’s gruff gallows humor — a kind of dark, wry sweetness — that may have enabled him to do what he did for so long. The piece also lays out a key insight about corralling former combatants together in common cause.

The cause? Dave’s lifelong pissed-off politics, to build better countries and target politicians and systems responsible for war’s life-shattering consequences, so they can’t just slink offstage to sow grief another day.

La Cuadra, Basrah, Iraq, Summer 2013

“Made a break through the desert inferno and twenty meters later entered the air conditioned kitchen. I took a few minutes to shoot the shit with my newest best friends, the also bunker-sequestered Demir and Darko. They are a couple Bosnians who work at the compound, training the Iraqi dog-handlers who, with their four-legged K-9 angels, scan the good earth here in southern Iraq for those little weapons of mass destruction: the land mines left behind by our guys.

“Darko, a Serb, and Demir, a Muslim, make an interesting argument for getting along with your former enemy. They fought against each other in their war. For a couple years, ironically, they both laid land mines to try to maim and kill each other. They were on opposite sides then, but are in the same bunker, now. It’s good work, if you can get it.

“The Bosnians, after hearing my idea of becoming a war correspondent, offered lots of what can only be described as sarcastic encouragement. ‘Yeah, well, write about what you know best, Dave. Tell everyone how you removed that one land mine in Vietnam the hard way.’ All this delivered in heavily-Balkan-accented laughter. I am still not completely convinced they aren’t Chechen terrorists. I am always checking to see if the pressure cooker is still in the kitchen. This time, it was there. I said goodbye to the guys, and asked them to please continue trying not to harm each other.

“Gallows humor helps the world go round in shitholes like this.”

CLOCKWISE (from upper left): One of Dave’s trainees work to fit a prosthetic arm in Sierra Leone in 2000; Dave (kneeling) poses with trainees in Havana, Cuba, in 1989; in Nicaragua in 1998; with his graduated technicians in Goma in the Congo in 2018; with a trainee in Sierra Leon in 2000; with prosthetic technicians in Russia in 1989; and posing with his trainees in Goma in 2018.

“‘Groundhog Day’ could have been filmed in Southern Iraq, 2013. Those of us who are here witness the slow, almost imperceptible change in this time of uneasy ‘peace,’ ten years after the beginning of the war. By any measure, this is not my first-time feeling like I just keep stepping into the same old pile of dogshit. It’s just like the feeling I had in the early ’80s, after buying a Chrysler K-car.

“I am working with the newly formed Iraqi government’s bureaucrats, officials who are working, in turn, to secure their fiefdoms. One problem is resolved only to have another follow on its heels. It’s just the culture of post-war anywhere, the nature of the beast.

“Who do we blame for creating this situation? I would start by laying blame at the feet of George W. Bush, his lying frontman Colin Powell, the United States Congress, the war profiteers and politicians. Evil in general. I also blame civilization, in general. We fill up our gas tanks and somebody dies.

“As a war correspondent, I don’t like the term ‘embedded.’ It sounds like a sex act of some sort. For me, it’s just another war zone. My eighth, if memory serves. And like those in those other scarred parts of the world, the war in Iraq hasn’t really ended. The mines are still in the ground. Kids keep getting blown up. Add to that the fact that the Sunni and Shia are locking-and-loading, getting ready for the big dance. It’s ugly now, and it’s gonna get a lot uglier.

“And let’s remember the numbers that have brought us to this point. Four thousand-plus dead American soldiers, airmen, and marines, with tens of thousands more disabled for life. Add to that the hundreds of thousands of Iraqis killed and maimed, and several trillion dollars, lost or wasted. The infrastructure in Iraq and the USA is in dire straits and needs to be rebuilt. As Powell warned, ‘If you break it, you’ve bought it.’ He could have been speaking about Detroit as well as Basrah.

“EPILOGUE: Although written with a bit of satiric license, at the end of the day Iraq is not now, not ever been, a joking matter. Since 2008, I have spent a little over 26 months ‘in country’ here in Iraq. The humor just provides some room for sanity in this writer’s mind. If I want to do my job, I’ve got to push out all the horrible things I have seen here and in previous war relief missions.

“And all joking aside, however much the politicians who voted for and supported the Iraq War would like to relegate it to the dustbin of history, we must not allow them to forget this tragedy. Ever. Not like we did after Vietnam.”

‘Which of you are Marxists?’

If they still keep old files —and I imagine they do—Dave Evans’ FBI file is likely NOT thin. You could see why, given the way the U.S. government has long justified its war-making. Dave kept the long view of revolutionary and societal struggles, given what he said way back in our 1985 interview concerning his visits to Central America.

He did not at all, of course, accept the Reagan-era claim that Central American conflicts represented an existential struggle between Western democracy and godless communism.

“We failed for the last 150 years to deal with oppression in Central America. The only thing we did is support dictators. We’re now seeing the results of that policy,” he said.

He told of meeting one Salvadoran rebel leader and his men. Asked them: “OK, which of you guys are Marxists? There are rumors all you guys are Marxists.” The leader of the rebels spoke up: “You don’t have to be a Marxist to fight a revolution. You just have to be hungry.”

Evans had a pungent observation of his own to make about an accusation sometimes leveled at him, since he was — due to the nature of his work and his passions — often ranging freely in conflict zones. He had more than once been accused of being “a Communist sympathizer,” he said. At that moment, we were flipping through a collection of photographs he had taken from his work in El Salvador. He pointed to pictures of Salvadoran children in camps.

“If all those kids are Communist, I’m sympathetic. I’m sympathetic to the Salvadoran soldiers. They’ve also been maimed by the war.”

Blue sky

People who knew him well may wonder if Dave drank himself to death, Kee writes. Given all he had seen in his life, you might understand why. But he hadn’t had a drink of hard liquor in a year as his health challenges mounted, she said. He had a series of kidney infections and then a bleeding ulcer, possibly from bad water or food.

“I’m not saying that Dave’s hard living and hard drinking did not contribute,” she said, but drink didn’t kill him outright.

One wonders, though, about the toll of all the things he had seen in his life, from conflicts and clashes across the world. All the broken bodies he and his teams sought to repair. Up until the last, Dave was willing to go any place in the world that needed him, said Kee. “He still gets emails from former students and patients from all over the world.”

Kee was unsure whether to include this last bit. Once you read it, you’ll realize why I could never not use it.

“I don’t think Dave ever told anyone else this,” she wrote.

Recall that December day in 1970, when an 18-year-old West Virginia teenager placed his foot on a mine intended for any random soldier passing beside a rice paddy. Dave’s old life ended in a shuddering blast. He landed on the ground. His eyes popped open. Kee describes what Dave told her and which she is now telling to anyone for the first time.

“He saw the most beautiful blue sky he had ever seen,” she said.

He felt a voice speaking to him, said Kee. “God spoke to him and told Dave he would give him another 50 years, if he used that time to help people and make a difference in the world.”

When he first described that moment to her, Kee told Dave it had been a near-death experience. Being Dave, he answered: “Don’t give me that woo-woo, hippie-chick shit.”

But here’s the thing. Dave died at age 68.

It was 50 years later from that day in Vietnam.

POSTSCRIPT

Dave Evans’ ashes were scattered on Kayford Mountain in the heart of West Virginia in late July 2021, by Dave’s two remaining brothers, his children and Kee Adams Evans.

This story is dedicated to Dave’s three children.

Douglas John Imbrogno is a lifelong storyteller in word and image. He is editor and founder of WestVirginiaVille.com

TRAILER

Here is the trailer for “The Wake Up Call,” a film about Dave Evans’ life by award winning documentarians Alison Gilkey and Eric Neudel. The film will be released later this year: https://vimeo.com/505430628/014f789182

AUGUST 2021 ISSUE of WestVirginiaVille.com

1) EDITORS/NOTE: Hellzones & Heroes, Painters & Clouds, Gardens & Grief

2) HERO OF THE OPEN HEART: The Long, Strange Trip of Dave Evans’ Notable Life

3) BACK/THEN: On the Bad Streets of Ann Magnuson’s Charleston Upbringing

4) MEMOIR: ‘The Garden and the Grief’ by Connie Kinsey

5) ART/WORK: Sharon Lynn and the Paths Taken

6) PHOTOSHOW: A high-up visit to Robert Singleton’s WV studio

7) VIDEOS: The Pillars of the WV Climate Alliance

FREE SUBSCRIBE AT:WestVirginiaVille.substack.com

RELATED

COVERSTORY: CHARACTERS: “When Earl Went to War”: april17.2021: American men of Earl Goodall’s generation are famously not forthcoming about their psychological states or what it’s like to go to war, people dying in front of and beside you. But this Korean War vet communicates all you need to know about that ‘Forgotten War.’

FREE SUBSCRIBE to WestVirginiaVille’s e-mail newsletter:

WestVirginiaVille.substack.com

A view of life based in the hills of West Virginia, yet often ranging well beyond its borders in space and in time. | A multimedia web-magazine edited by DOUGLAS JOHN IMBROGNO with guest contributors.

7 Comments

admin

Thank you for your powerful memory of the guardian angel that was Dave Evans, Michael. Peace | Editor: Douglas John Imbrogno

Anonymous

In May 13 1980 I was hit by a car and lost my left leg above knee in ridgeview wv I was 17 years old in June of 1980 I met Mr Dave Evans while he was a technician at j.e hanger Charleston wv Dave Evans was the most professionist and the kinda man I’d ever met being so young at 17 years old and losing my leg I was scared and thought that I’d never walk again think god all those thoughts and fears were soon to fade away think you Dave Evans rest in peace my dear friend ill never forget you taught me too walk again and till this day February 4 2025 you built me the best leg I ever had you are so well loved worldwide and missed by so many and are remembered and inspired by countless of people worldwide by family and friends this written from my heart again rest in peace you certainly answered God’s calling sincerely always your friend Michael Linville

admin

A heads up to all who commented on this Dave Evans story. A slightly rewritten, shorter version of this article will be published in the JUNE 2022 issue of WestVirginiaVille. It is timed to promote the June 23 West Virginia premiere of a documentary about Dave’s life, “The Wake Up Call,” at the Culture Center Theater in the state Capitol Complex in Charleston WV, an official event of the citywide 2022 FestivALL Charleston. The documentary won “Best Content” award for a feature documentary at its world premiere in April 2022 at the Boston International Film Festival. Tickets to the FestivALL screening are $10 — or $5 for veterans — and a catered reception takes place 6 pm in the Great Hall. A panel discussion follows the screening on stage, to talk about Dave and the issues his life’s work raises that remain pertinent today. GET TICKETS AT THE DOOR or IN ADVANCE AT THIS LINK: https://bit.ly/thewakeupcall-tickets

admin

His was a Nobel-worthy life indeed, Rose! Thanks for your note.

Rose Edington

Doug — thanks for writing about Dave Evans! He deserves a Nobel Peace Prize.

admin

Dear Kyle: Thank you for commenting on the article with how Dave inspired your own life. Really cool to hear. Bravo to you for all the good work you describe. Is Bobby still with us? If so, would like to get the article to him. Be well.

Kyle Workman

I loved Dave Evans, he taught me so much. I was one of the Vietnam Vets with anger issues. Hel calmed me down and sent me on my way. I formed a VVA Chapter in logan, WV. and brought the first rural Vet Center to Logan County that had to be self funded. Come to find out it was the first in the USA. Dave Evans inspired me to do that. Bobby Mueller was my inspiration for the West Virginia Veterans Memorial on the State Capitol Grounds in Charleston, WV. I was so fortunate to have these two heroes in my life.